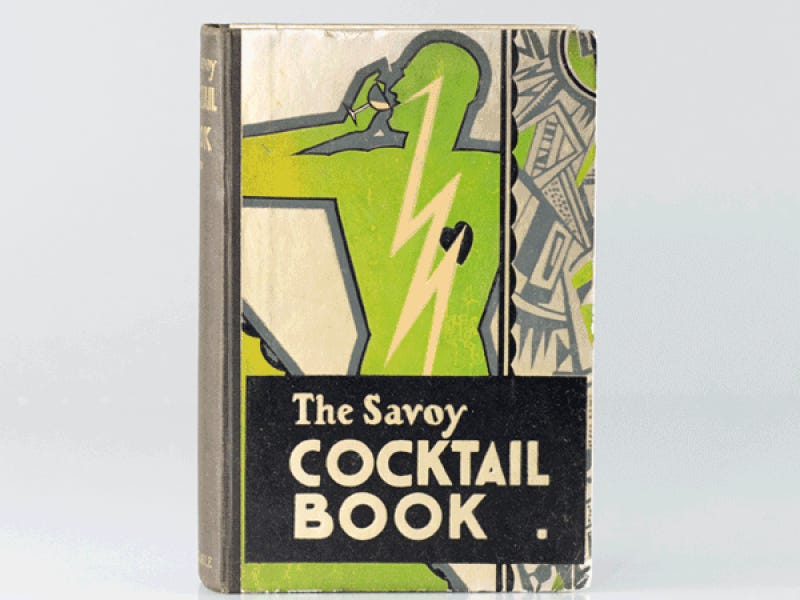

Abebooks, the on-line market for bibliophiles, recently announced that "one of the fastest growing areas of the rare book world is vintage cocktail books," with the 1930 Savoy Cocktail Book "considered to be the quintessential cocktail book from this era. Its art deco cover design is to die for."

I own a first edition of the Savoy Cocktail Book, and the design is indeed striking, if not quite life-threatening - more than can be said of the contents, some of which would leave one's liver a smoking wreck.

However, aside from the Gin and Tonic and Bloody Mary, cocktails don't seem to be of much interest to today's jeunesse doree, let alone such anciens as myself.

Instead, now that the weather is warmer, most late afternoons will find me on our balcony with a few friends, indulging in the custom known as the apero, an early evening rendezvous for an aperitif, intended to sharpen your appetite for the dinner to follow.

The apero has something in common with Happy Hour though it isn't quite the same. For one thing, the hour following the end of the working day is too early for an apero. (Traditionally, the working man spent those hours, known as le cinq à sept - the five to seven - enjoying a pause crapuleuse or erotic dalliance with his lover before continuing home for dinner with the family.) It depends on a culture where people eat at times by which the staff of most American restaurants are tucked up in bed with their cocoa.

Until tourists began to pour into Paris after World War I, cocktails were unknown. Cafés served only coffee, the various eaux de vie, and the infusions of wines and herbs known as aperitifs and digestifs. Orders for an Old Fashioned or Cosmopolitan were met with blank stares. Martini was sweet, red, smelled of sage, and was served over ice with a slice of orange - while, if your pronunciation was off, an order for beer could get you Byrrh, a similar infusion, but flavoured with quinine.

The closest to a "mixed drink" was cafe corrigé— black coffee "corrected" with a dash of cognac; the fine à l'eau— brandy diluted with a little water —and the Toddy or Punch (pronounced ponch). Combining rum, hot water, sugar and lemon, this supposedly protected against the common cold, and was a favorite of Ernest Hemingway. "And we sit outside the Dôme Café," he wrote to Sherwood Anderson, "warmed up against one of those charcoal braziers and it’s so damned cold outside and the brazier makes it so warm and we drink rum punch, hot, and the rum enters into us like the Holy Spirit."

The Dome cafe with charcoal heaters.

For the late adoption of the cocktail in France, blame the church. The need for sacramental wine made it a major consumer, with abbeys guaranteeing the supply. While some orders of monks stuck with wine growing and bottling - a monk, Dom Perignon, is credited, erroneously, with inventing champagne - others experimented. The Benedictines and Carthusians distilled alcohol and used it to macerate herbs and roots, creating potions to aid digestion - digestifs - and improve appetite - aperitifs. Benedictine and Chartreuse still bear their names.

Secular Anglo-Saxon brewers concentrated on producing the grain spirits on which cocktails are based. When Prohibition halted that trade in 1920, drinkers turned thirstily towards more liberal Europe. “To a certain class of American,” wrote Jimmie Charters, barman at the Dingo, the Jockey, and Harry’s Bar, “drinking in excess became an obligation. No party was a success without complete intoxication of the guests.” Journalist Waverley Root, arriving from New York to take up a job on the Herald Tribune, decided to follow what he understood was a French custom and ordered a bottle of vin rouge with his first continental meal. The waiter didn't feel it was his business to explain that even the French didn't drink wine with breakfast.

Bars Americains appeared all over Paris, often manned by African-Americans, former soldiers who gravitated to France because of its indifference to skin color. The Savoy Cocktail Book became their indispensible reference, its 300 pages filled with recipes for highballs, toddies, fizzes, sours, juleps and coolers. They included the Corpse Reviver (Gin, Cointreau and absinthe), Satan's Whiskers (Italian and French vermouth, gin, orange juice and Grand Marnier) and the coffee-colored Josephine Baker (Cognac, apricot brandy, port, lemon zest and an egg yolk.) "Our epoch," announced Dutch painter Kees van Dongen in 1928, "is the cocktail epoch. Cocktails! They are of all colours. They contain something of everything. The modern society woman is a cocktail. Society itself is a bright mixture. You can blend people of all tastes and classes."

One potion that doesn't appear in the Savoy is also one about which I've always been curious. It's the so-called Montgomery Martini. Apparently Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery never went into battle with a superiority of less than seventeen of his troops to one of the enemy. Ernest supposedly had a shaker of martinis mixed up with those proportions - seventeen parts of gin to one of vermouth. The effects are not recorded - though they may explain why he felt Paris to be so particularly movable

“Er…that’s fourteen….no, fifteen….maybe I’d better begin again…..”

They sound so inventive and delectable. I would be under the table or talking in braille after 2 of any one of those.

Cocktails do appear to be popular here in Melbourne with jeunesse doree, for prices between $12 and $20 and with new names for them popping up every time one passes a bar.