“Deco” in French just means DIY - painting the spare room; laying a new stair carpet. Art deco, however, is something else: a revolution in design that swept the world after World War I. It transformed industrial design, fashion, architecture, graphic art and cinema, inspired New York’s Chrysler Building and Rockefeller Centre, Fritz Lang’s futuristic city of Metropolis, the automobiles of Studebaker and Buick, Tamara de Lempicka’s portraits, Ginger Rogers’ gowns, Coty perfume flagons, Radiola gramophones, and a million ashtrays, soda bottles, cigarette lighters, chocolate boxes, comic books and toys. Anyone confronted by its products might well echo journalist Lincoln Steffens on first visiting the Soviet Union – “I have seen the future, and it works!”

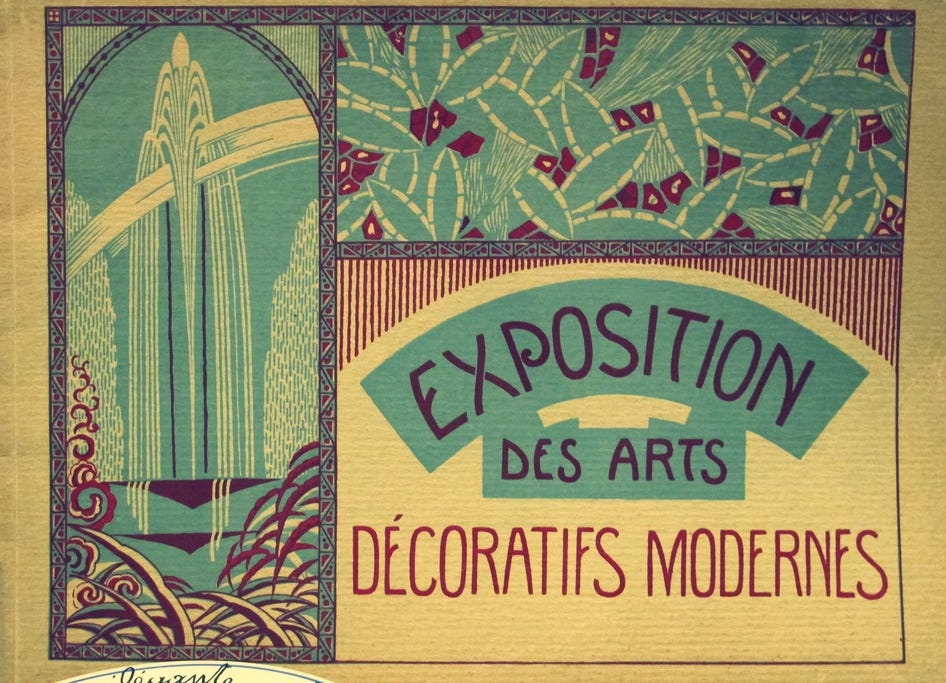

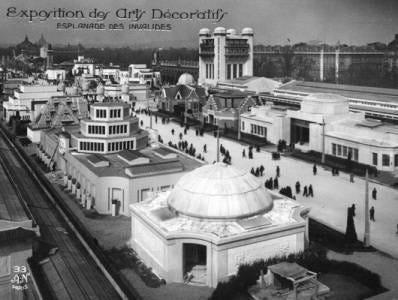

Art deco began as a French attempt to stem the rise of German design after World War One. New synthetic fabrics, chemical dyes and metal alloys threatened French manufacturers who prided themselves on using natural materials - silk, ivory, leather, silver, wood. With the Exposition International des Arts Decoratifs Modernes, France aimed to remind the world that, in design and craftsmanship, it remained supreme. Throughout the spring and summer of 1925, a village grew along the Seine. White plaster “pavilions,” many as fancifully detailed as wedding cakes, colonized the spaces below and around the Eiffel Tower. Most were sponsored by department stores or individual manufacturers, both French and foreign - although both Germany and the United States declined to participate. The Studio, Britain’s journal of record for the applied arts, found little to praise in its own pavilion, but acclaimed French invention. “The new ideas seemed to have come like a flood, carrying all along in its course.” Another visitor called the show “a Cubist dream city, or the projection of a possible city on Mars.”

Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, France’s leading designer of luxury furniture, had the task of making sure everyone respected the exposition’s high ideals. Unexpectedly, he faced a problem with his own countrymen. There was no agreement among them of what constituted a truly modern style. While they admired the functionalism and avoidance of decoration already appearing in cameras, wrist watches, cigarette cases and lighters, they were loath to discard the femininity of pre-war art nouveau, which adapted so well to everything from architecture to jewellery.

For a nation not known for consensus, they took relatively little time to agree. Essentially, they returned to the classicism in which all of had been educated, and for which the French public since the time of Napoleon I had showed such affection. An architect from ancient Greece would have felt right at home with these fountains, gardens, courtyards, decorative friezes and statuary groups. The synthesis of Greco-Roman design and machine age technology became so instantly recognizable that nobody bothered to name it. Not until the nineteen-sixties would scholars agree on the title “art deco.”

Aside from the pavilions of Galeries Lafayette and other department stores, manufacturers created the biggest splash. Citroën automobiles paid for a modernist display of lights on the Eiffel Tower. Glassmaker René Lalique built a towering fountain that lit up at night. The exposition didn’t stop at the Seine. Shops lined the Alexandre III bridge. Couturier Paul Poiret, hopeful of retrieving his pre-war reputation, sold his collection of modern art to buy three barges. Mooring them alongside the exhibition, he turned them into showrooms for his gowns, and for the textiles, furniture and accessories of his Atelier Marine workshops. An esplanade ran along their roofs, descending in wide steps to the waterline, where visitors arriving by boat were invited to alight.

The Exposition achieved its aims, only to see the crash of 1929 kill the market it created. Meanwhile, American manufacturers duplicated French designs using the synthetics Germany pioneered. With rayon, women could afford dresses as vivid as anything seen in a Paris fashion show. Chromed steel, originally a substitute for silver in the detailing of automobiles, emerged as a material in its own right. Bakelite and other resins brought the appearance of ebony, ivory and tortoiseshell to hair brushes, picture frames, radio sets.

Hollywood provided the perfect growth medium for this visual virus. Couturiers and architects, having learned the style in Paris or Berlin, brought it to Hollywood, where it suited thpse melodramas Noël Coward called “tales of high life and low loins.” That such French pioneers of the cinema as the Lumière brothers and Charles Pathé were indirectly responsible for the downfall of art deco is just one more irony on the heap that buried the 20th century’s most audacious and innovative style.

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in Swing Time (1936), designed by Carrol Clark.

Frank Lloyd Wright understood deco. “I believe,” he wrote, “that romance—this quality of the heart, the essential joy we have in living—by human imagination of the right sort can be brought to life again in modern industry. Creative imagination may yet convert our prosaic problems to poetry while modern Rome howls and eyebrows of the Pharisees rise.”

Well, me too, Frank – but ot seems we’re in the minority, even in France, where, apparently, the centenary will pass without much in the way of celebration.

Thanks for this update. Much appreciated. I'm glad the centenary isn't going entirely uncelebrated. I'd very much like to see one of those pavilions recreated on the Champ de Mars.

I loved that period. If I could time travel that is on the top of my list. John your knowledge of simply everything continues to astound me.