Paris is a compact city. You can cross it, from Montmartre to Montparnasse, in half a day. But this has a downside. It’s easy to surround and search. Disreputable elements can be rounded up. There is a word for such an operation – it’s called a razzia.

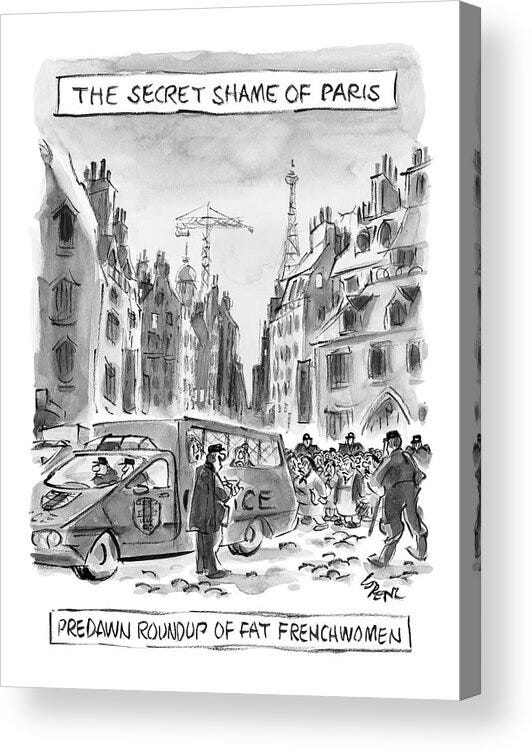

At times it has been a joke. There’s Lee Lorenz’s famous cartoon explaining why there are so few fat women on Paris streets.

Mostly, however, it’s more sinister. The Nazis, for example, found it useful in suppressing the Resistance during World War II. When Jean Moulin held his first meeting of a united underground, he chose a spot near three Metro stations, and plenty of escape routes across the roofs. He was still betrayed. This is not a city in which it’s easy to lose oneself.

What’s been happening this week is neither as amusing as the Lorenz joke nor as brutal as the Nazi round-ups. The police have begun clearing people whose presence on the streets would be undesirable as the Olympic Games looms.

According to the Guardian, “The collective expulsions and the dismantling of tent camps in and around the city had intensified since April last year, and 12,545 people had been moved in the last 13 months. Police were also cracking down on sex workers and drug addicts The Île-de-France region has been emptied of some of the people that the powers that be consider undesirable. ”

How do the Parisians feel about this?

A while back, I wrote a piece about mendiants – beggars – and tried to explain how we see them as a resource. We drop money into their cups, and feel virtuous in return. It isn’t charity so much as a transaction. Going further, however, can have its dangers. In Jean Renoir’s film 1932 Boudu Sauvé des Eaux/Boudu Saved From Drowning, a kindly bouquiniste rescues a tramp after he tries to drown himself in the Seine. Taking him home, he attempts of “civilize” him - without success.

So we tolerate the homeless rather than embracing them. Most markets won’t give them food outright but don’t mind them scavenging for unsold produce. The police won’t eject squatters during the winter months. Nor do they hassle those who turn doorways into bedrooms, leaving their bedding and sheets of cardboard in place, confident they won’t be disturbed.

The local version of the Salvation Army used to circulate through the central arrondissements in a bus each night, collecting those sleeping rough and taking them to a facility at suburban Asniers where they were given a shower, a meal, medical treatment if needed, a bed, and advice on how to enter a system that might give them, in time, a permanent abode. Most were back on the streets next morning.

There’s a sense among Parisians that, even though they are not like us, the homeless, even those who have no legal right to be here, are citizens just the same. And to deprive them of that right, that status, to make the city more pleasant for people who are only here for a few weeks? How will that play? On verra, as they say. We’ll see.