The Stupid Leave Them.

It probably won't surprise anyone to discover that, according to a recent poll, France spends more time eating and drinking than any country in the world; more than two hours a day per head of population, as against the UK's 1 hour 18 minutes, Australia's 1 hour 31, and the United States' 1 hour and 1 minute.

This doesn't mean that the French eat more; just that they go about it differently. The mechanics of eating mean far more to the French than what they actually consume. As Henry Higgings says in My Fair Lady, "the French don't care what they say, so long as they pronounce it correctly." The time and expertise required to eat a snail, let alone prepare it for the table, is out of all proportion to what goes into one's mouth. A souffle is just an omelette that takes an hour to prepare. They fuss about the hundreds of cheeses but seldom eat more than a sliver. And let's not even think about truffles.

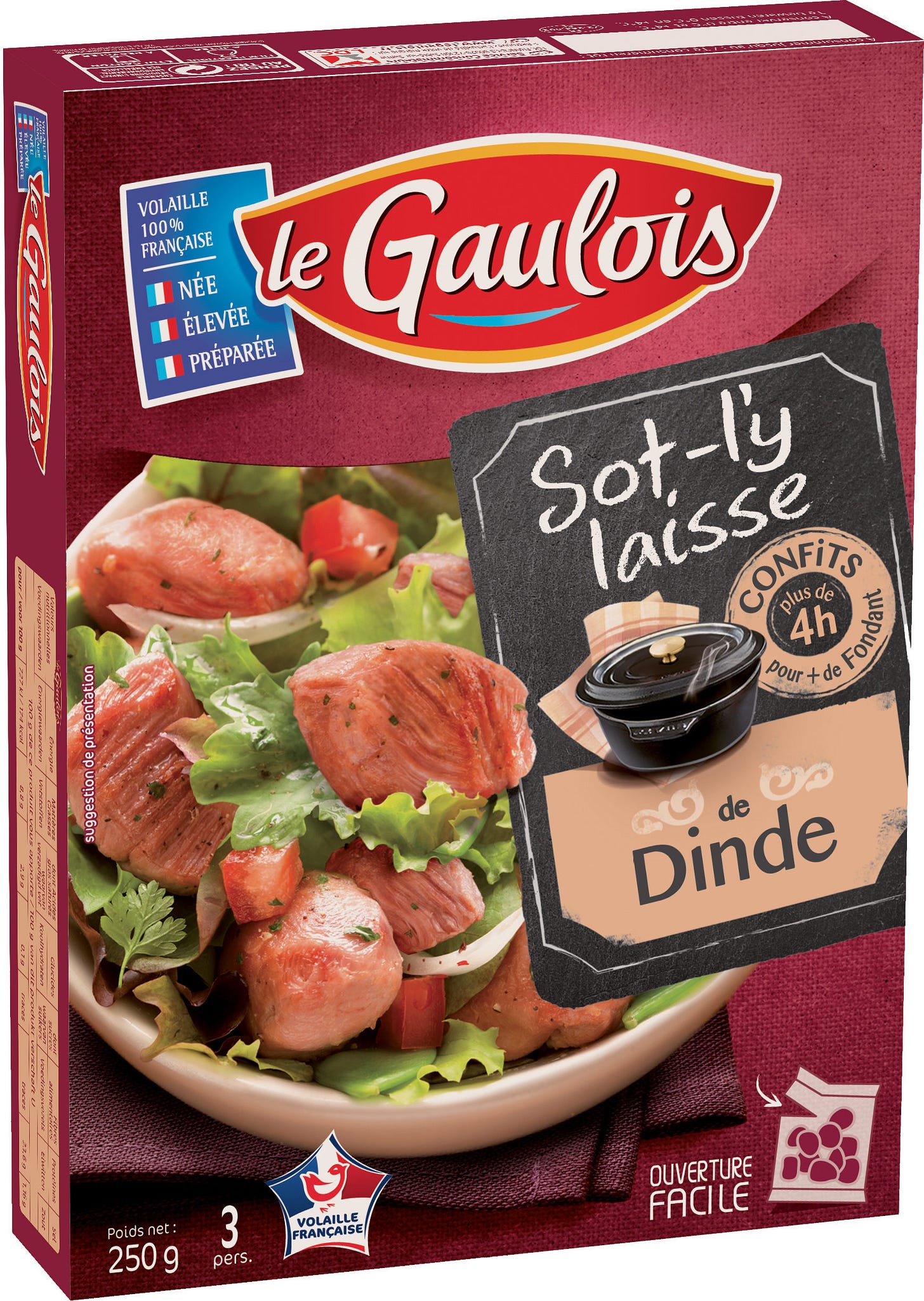

The American or Australian ideal of the "good feed" - pizza, hamburgers, ribs, steak - is predicated on ease of eating - whereas the French take pleasure in the difficult; slow food, not fast. The more complex the dish to prepare and the more inaccessible the ingredients, the better. Not everyone can be bothered digging out the tender "oysters" of meat found near the backbone of a chicken or turkey. But packs of these are available in most French supermarkets with the somewhat smug label Le sot- l'y-laisse/The stupid leave them.

It hasn't always been like this. Or, rather, there was always an option to pig out, if that was your taste.

The French recognise three categories of eater - the gourmet, the gourmand and the gastronome.

Gastronomes barely eat anything. Conerned only for taste, they just nibble and move on.

Gourmets come closest to the norm. They enjoy food, take pleasure in the act of eating, even occasionally over-indulge, but don’t think much about it between meals.

Which leaves the gourmand; the greedy, the gorger; the glutton.

Normally, I wouldn't have classed the great chef de cuisine Georges Auguste Escoffier among the gourmands. There's nothing like spending the whole day in the kitchen, stirring, chopping, tasting, to ruin one's appetite. He almost defined the gastronome in some of the dishes he created, which seemed intended more to be admired than eaten.

For a 1908 dinner at which the notoriously priapic Prince of Wales was guest of honour, he created Nymphs à l’Aurore/ Nymphs In the Dawn. In clear champagne jelly, tiny morsels of meat, tinted pale pink - actually frogs' legs - peeped from green fronds of water cress in a tantalising suggestion of female creatures wreathed in water plants. What kind of boor would plunge his spoon into a dish as delicate as that?

Escoffier and the Prince of Wales about to eat lunch.

But just when I'd fixed my mind on an image of the great chef sitting down at the end of a hard day in the kitchen to a cup of bouillon and a soft boiled egg, I found this description of what he and a few friends ate during a holiday in the Haute Savoie just after World War I.

"Our dinner was composed of a cream of pumpkin soup with little croutons fried in butter, a young turkey roasted on the spit, accompanied by a large country sausage and a salad of potatoes, dandelions and beetroot, and followed by pears cooked in red wine and served with whipped cream. Dinner next day consisted of a cabbage, potato, and kohlrabi soup, augmented with three young chickens, an enormous piece of lean bacon, and a big farmhouse sausage. The broth, with some of the mashed vegetables, was poured over slices of toast, which made an excellent rustic soup. To follow, we were served with a leg of mutton, tender and pink, accompanied by a puree of chestnuts. An immense, hermetically sealed terrine gave out, when uncovered, a marvelous scent of truffles, partridges, and aromatic herbs. This terrine contained eight young partridges, amply truffled and wrapped in fat bacon, a little bouquet of mountain herbs and several glasses of fine champagne cognac. The next day's luncheon was composed partly of the trophies of the previous day's shooting" [apparently 'three hares, a very young chamois, eleven partridges, three capercailzies, six young rabbits, and a quantity of small birds.'] "We did not have any hors-d'oeuvre but instead, some char [a freshwater fish, resembling a salmon], cooked and left to get cold in white wine from our host's own vineyards."

And he doesn't even mention dessert.

Such a humongous meal! It made me tired to think even of eating a bit of it! I’m glad some things have changed over the years!

I always just look forward to onion soup gratinée, crème brûlée, and crusty bread—always with French butter. Guess I have a peasant’s taste. When I really splurge, I get burrata cheese with it!!