Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Big crowd tonight.

Charles Zidler (manager of the Moulin Rouge): Too big, thanks to your poster. Oh, I know I'm making millions, but I liked the Moulin Rouge as she was, lighthearted and hot-blooded, a little strumpet who thought only of tonight.

Script for 1952 film Moulin Rouge. Anthony Veiller and John Huston.

Someone asked me recently which would be more suitable as an introduction to Paris nightlife for her daughter, the cabaret at the Lapin Agile or the supper show at the Moulin Rouge. I recommended the latter, but not without a sense of incongruity. There was a time when the last thing you’d want for your daughter was to see the cancan.

First, to clarify the pronunciation, “can can” doesn’t rhyme with “man man.” It’s closer to “con con,” or, with French intonation, “cong cong.” In 19th century slang, to ‘can can’ meant to circulate a canard or malicious story; to create gossip; a scandal. No surprise, then, that the high-kicking dance of the belle epoque belongs in that area of French life designated louche, ie, shady or dubious.

But it’s precisely for that reason that audiences still crowd into the Moulin Rouge and Paradis Latin where a performance by platoons of chorus girls forms the centrepiece of a high-priced night out. Nobody would pay to see the once-controversial tango or waltz performed, no matter how expertly. The cancan survives on one characteristic – naughtiness.

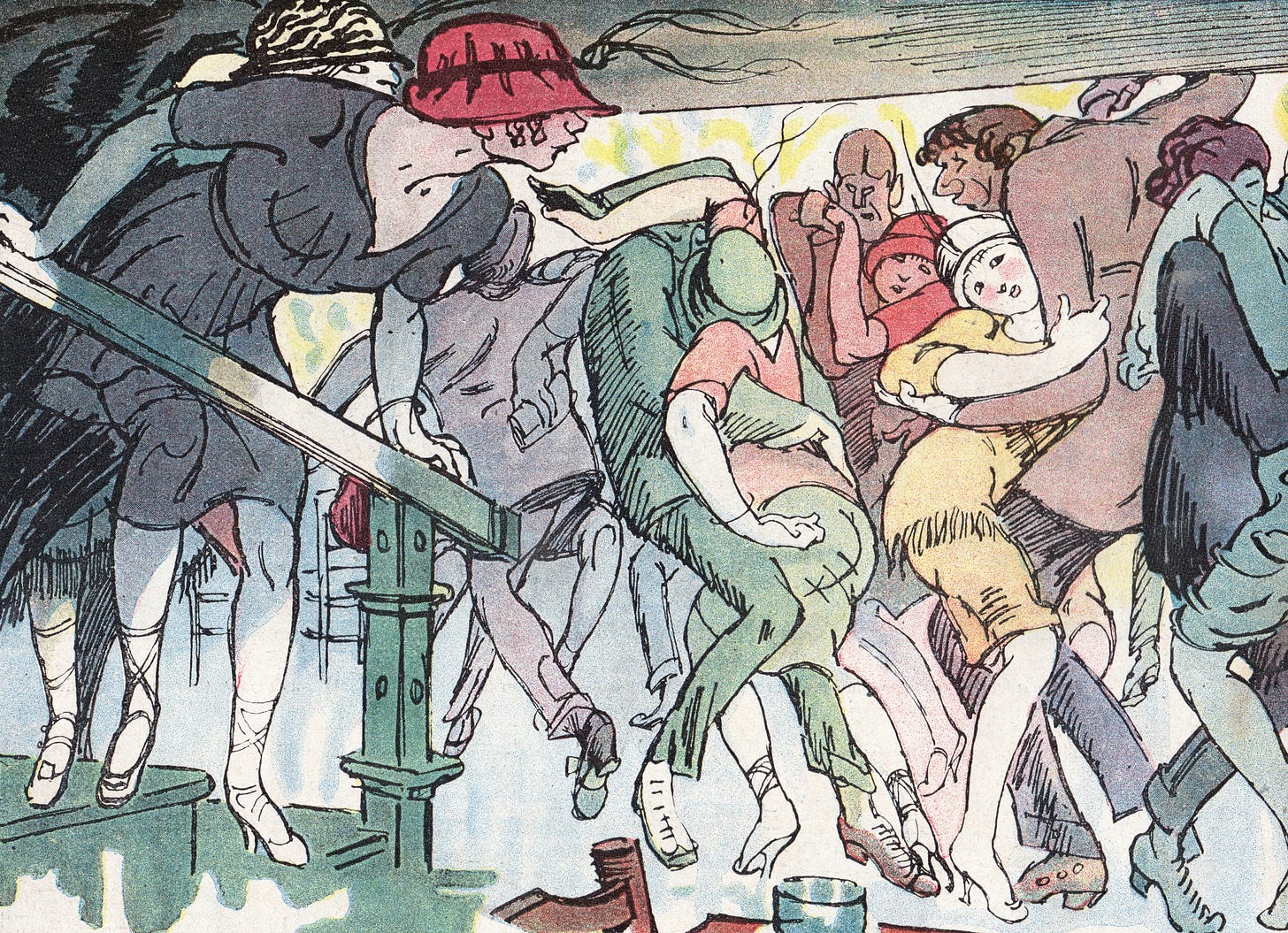

When it emerged around 1830, most dancing took place in public halls called bals musettes. Invariably jammed, they offered no room for fancy steps. Instead, mobs of men and women jigged round the crowded floor in the java, a dance separated from vertical sex only by a few layers of fabric. The woman hung on the neck of a man who, cigarette wedged in the corner of his mouth and beret jammed on his brilliantined head, stared over her shoulder and, clutching her buttocks with both hands, ground his pelvis into hers. Intent only on a few minutes of sensation, they did so in silence. The etiquette of the bal musette forbade conversation. No “Do you come here often?” or “How do you like the band?” Clients came there for one thing only – the grind.

Bal musette in Montmarrtre, 1920s.

Men who couldn’t find partners at a bal musette revived the then-outmoded cancan, originally known as a chahut or “uproar.” Bursting onto the floor, they kicked wildly, did cartwheels, shouting and jostling other dancers, like the jitterbugs and jivers of the nineteen-forties. Sometimes they were joined by women bored at being groped by sullen, inarticulate dopes.

Inevitably, someone saw a way to make money. Jean Renoir dramatised the moment in his 1954 film French CanCan. Showman Danglard, played by Jean Gabin at his most mischievously charming, spots a pretty laundress named Nini fooling around at a musette and decides to build a show around her. He takes her to veteran hoofer Guibolle (slang for “leg”) and asks her to teach Nini and her friends the cancan. Guibolle thinks he’s crazy. For one thing, it’s way out of date. For another, modern girls don’t have the flexibility. Here’s that scene,

Despite Guibolle’s scepticism, Nini and the girls become expert. Not that there is much to learn. Aside from the porte d’armes, the main steps are the battement or high kick, the rond de jambe , a rotation of the lower leg with knee raised and skirt held up, the roue or cartwheel and, most spectacular, the grand écart , a flying leap, ending in the splits. All of these benefited from a detail Renoir omits from his film; women of the time didn’t wear knickers. Or, rather, they wore pantalettes, which covered the legs but not the central portion, a crucial detail at a time when toilets, where they existed, were holes in the floor over which one squatted.

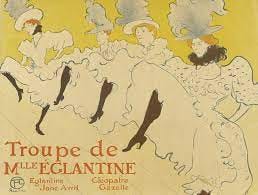

Its proprietor called the new Moulin “The Paradise of Women” but the title was misleading. Only men were admitted to the shows. Women had no role except to entertain them with the can-can. A troupe rushed onto the floor, whooping, turning cartwheels, and flourishing their petticoats. Their star was Louise Weber, known as La Goulue (the Glutton) for her habit of snatching food from clients’ tables. Spotting the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, in the audience, she famously shouted “Hey, Wales, you buy us champagne?” She competed with Nini Pattes-en-l’Air (High-Kicking Nini) and La Môme Fromage (Little Miss Cheese). The more limber girls executed the porte d'armes (Shoulder arms), grabbing an ankle and raising a leg almost to the vertical, displaying everything.

An American visitor in 1927 praised (not very accurately) “a big, flashy revue here. 100 girls who do not wear even a bangle. A band plays in the foyer during intermission. Everyone leaves their seats, promenades and drinks. Also a roof garden on top of the building, and you can dine here. Also a naughty exhibition of oriental dancers. How tame by comparison is theatre-going in America!”

Orchestra leaders found the perfect cancan music in the Galop Infernale from Jacques Offenbach's 1858 Orpheus in the Underworld. Its brevity – only six minutes – is perfect for so strenuous a dance, and its climax, all cymbals and bass drums, matches the orgy of grands écarts with which performances traditionally conclude. Musicians got used to the yelps, shouts and screams emitted by the dancers, and just played louder, contributing to the sense of uproar without which a performance never seems authentic.

It’s ironic, but also appropriate, that a dance that’s barely a dance has become one of the most enduring monuments to a period notorious for its triviality, excess and pursuit of pleasure. This aspect offended Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and his wife when they spent a day Twentieth Century-Fox in Hollywood in September 1959. As Frank Sinatra and Shirley MacLaine were filming Cole Porter’s Can Can, the dancers, led by Juliet Prowse, treated their visitors to the cancan before the formal all-star lunch. But Khrushchev was not amused. "The face of mankind is prettier than its backside,” he grumbled. “The thing is immoral. We do not want that sort of thing for the Russians."

Incidentally, few of the dancers at the Moulin Rouge these days are French. Tall, athletic, high-kicking women are thin on the ground in modern France. The flower of the current flock come from Australia.

Great read. Peter & I went there a few years ago. A sea of tourists of course. We paid for food so we could get a decent seat. Interesting evening. The show was very good.