As mentioned in an earlier posting, the recent rediscovery of a fat file labeled “Miscellaneous” has reunited me with quantities of writing dating back to the ‘nineties. The following was a posting for a blog created in the early 2000s by HarperCollins to “humanize” its authors. Of its success in doing so, I can only speculate.

A bump on the doormat announces the arrival of the morning mail. Our cat Scotty runs up the hall and stares at the door expectantly, knowing my opening it will allow him a brief escape into the alien world of the winding staircase, and a glimpse, down six flights, of a Paris in which he, rooftop-born and bred, has never set paw.

Being raised in an Australian country town caused me to allocate exaggerated importance to mail. It meant the outside world still knew of my existence. “And none will hear the postman’s knock/Without a quickening of the heart,” wrote Auden in his commentary for the film Night Mail, “for who can bear to feel himself forgotten?”

And a bump was doubly exciting, since it always meant books.

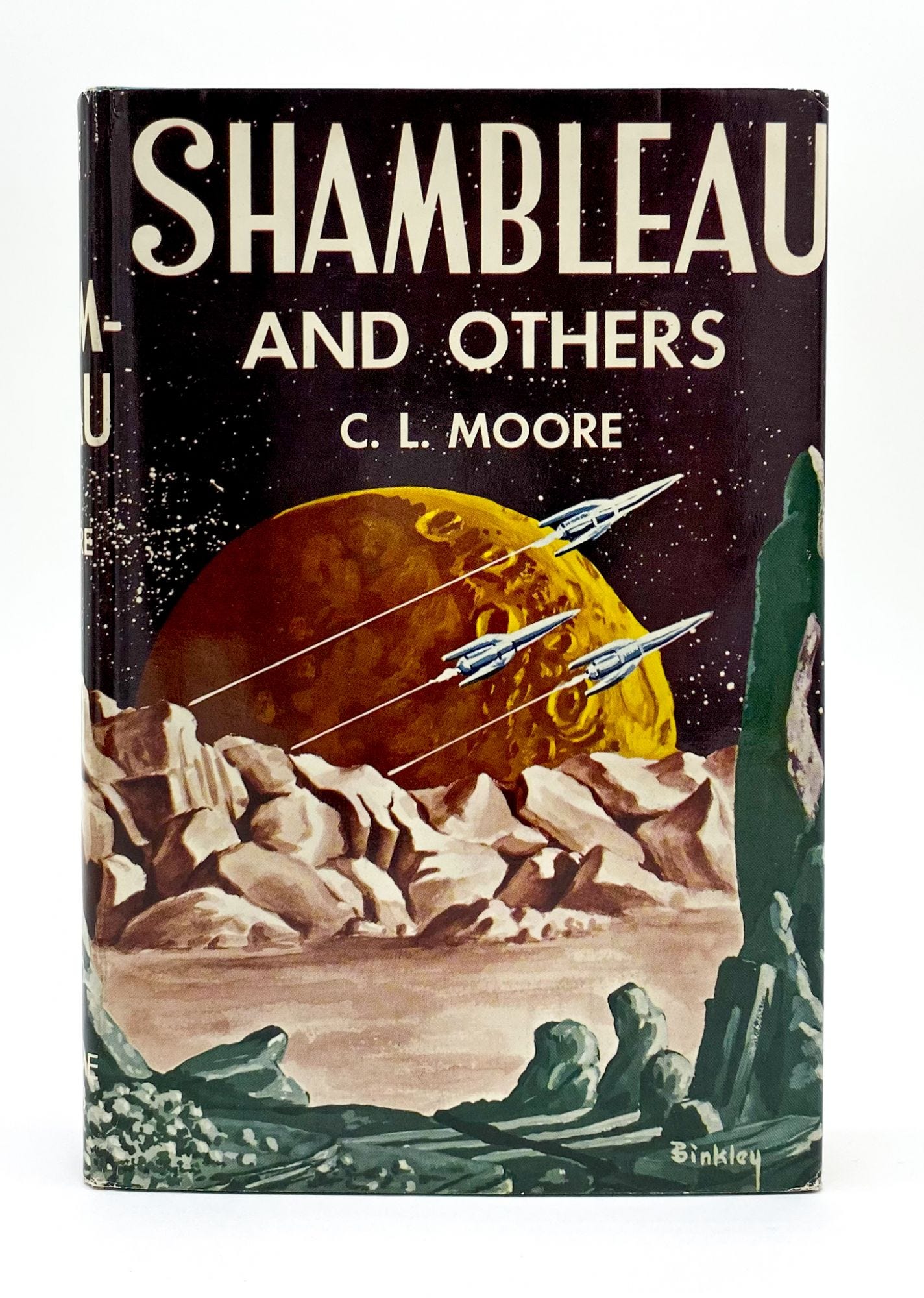

Today it’s Shambleau and Others, a collection of science fiction stories by Catherine Moore, published by the Gnome Press in 1953 – just about the time the sf bug first wriggled into my blood. This nice copy of the first edition was snatched from the flood that pours hourly through eBay. On the dustwrapper, sharp as on publication day, three impossibly sleek rockets lance up from a rocky landscape against a black sky and a looming, cratered moon. A ‘fifties idea of space travel, as quaint as that year’s finned, chromed Cadillac Eldorado.

I dip into the first story, Black God’s Kiss. “Joiry’s lady glared back at him from between her captors, wild red hair tousled, wild lion-yellow eyes ablaze… ‘Come to me, pretty one,” he commanded. ‘I wager your lips are sweeter than your words..’ ” Well, it read like frozen music at fourteen. But space opera, in common with the pulp paper of the magazines that printed it, turns yellow and crumbles almost before the ink’s dry.

I shelve the book between Anne McCaffrey’s Decision at Doona (inscribed “To John, for courage above and beyond the call of a writer’s function…” - “courage” being smuggling then-forbidden birth control pills into Catholic Ireland for her daughter), and Michael Moorcock’s The Final Programme.

From emails, I jump to eBay, checking what my overnight searches have turned up. A first edition of Robert A. Heinlein’s The Green Hills of Earth? Sounds good. Terrible tripe, of course. In the title story, a blind space poet, tending an atomic rocket gone bad, reels off stanzas of verse so leaden that no radiation could possibly have penetrated them - like this couplet about an imaginary once-inhabited Mars. “Along the Grand Canal still soar the fragile Towers of Truth;/Their fairy grace defends this place of Beauty, calm and couth.” Oh, dear. But the dustwrapper looks great, and I post a bid.

Of the thousands of books in my collection, ranging from Wells’ The Invisible Man and First Men in the Moon through John Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids, Asimov’s The Naked Sun, Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, few date from later than the mid-sixties. They’re reminders of a time when we thought science was the solution to society’s ills rather than a contribution to them. Journalist Lincoln Steffens, returning from new-born Soviet Russia in 1919, proclaimed “I have seen the future, and it works!” Apparently not.