For those of you who aren't fans of opera, the death of counter-tenor James Bowman won't mean a lot. It probably wouldn't for me, had I not attended a London production of Handel's Semele in 1971.

Only recently off the boat from Australia, I still harbored all the prejudices of a ragbag education in classical music, which, having been arrived at by the back door, via the dissonant jazz of Stan Kenton, was strong on the avant garde and those orchestral works that can sound like a truckload of scrap metal being emptied down a marble staircase.

Fortunately, my companion of the time was a singer, and took me in hand, so that, when the curtain went up on a set like an 18th century chocolate box, with frou frou costumes and gadgetry that whisked singers from earth into clouds solid enough to sit on, I didn't head for the exit.

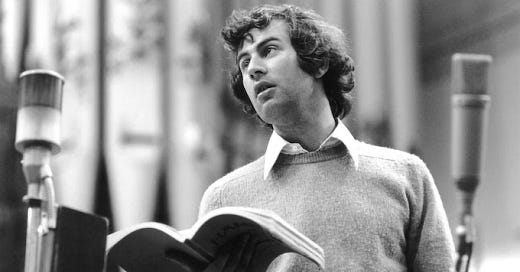

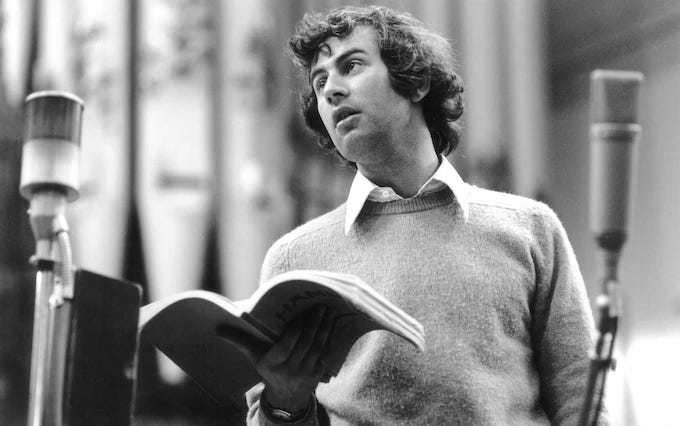

After the first half hour, however, I was hooked, so the arrival on stage of James Bowman, dressed head to foot in blue silk, after Gainsborough's The Blue Boy, caused no more than a raised eyebrow. Until, that is, he started to sing.

Not everyone is comfortable with the counter-tenor voice. A boy singing falsetto is one thing, but after puberty a man is supposed to put his voice where his balls are. Italian composers of the cinquecento, loath to have only tenors and baritones to work with, ensured a supply of adult sopranos by turning the more talented trebles into castrati, and, while this practice had ceased, for a man to sing like a woman still causes some to fidget.

Bowman had only one aria that night, but it was Where e'er You Walk, one of the baroque Top Forty. Disposed by his costume and height to be impressed, we were ravished by his voice. Our standing ovation stopped the show - literally, since, during the interval, an apologetic management announced that the lead soprano had become "indisposed". (She might genuinely have been ill, I suppose, but there was much murmuring in the bar.) We waited for an extra hour while her understudy was dragged away from a quiet evening with the telly.

After that, Bowman became a fixture of our musical landscape. Since my friend sang in the choir at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival, we saw and heard him often, including a late night solo recital at a nearby medieval church - dedicated, he said, to his "silent audience", pointing to the wooden cherubs carved into the ancient rafters.

He also turned up, to our surprise, in an Oxford performance of the Messiah. Staying with friends, we went with them, without great expectations. I still remember our unison "James Bowman?" when we saw his name in the programme. And he was, of course, the hit of the evening.

Here he is at his best, in a duet with Michael Chance, who replaces him as Britain's premier English counter-tenor, as Bowman supplanted Alfred Deller. The words of Henry Purcell's anthem speak of "instruments of joy that skillful numbers can employ". For me, his voice was such an instrument. Until I heard him and others of the English vocal tradition, I never knew music could make one weep with pleasure. See what you think.

Stage fright - what the French call "trac" - has been the end of many a promising career. Still, he has clearly chosen a less precarious profession.

Hello John,

Can I ask you something? About Eng. tense. I notice you have used Past tense and Present tense deliberately (and very carefully, too) in the text. They all make sense. How about in one sentence, do you think tense is necessary going to be consistent no matter the circumstance?

Thanks.