“Must we burn Sade?” Simone de Beauvoir wrote back in 1952. At a time when the writings of the Divine Marquis were universally demonized, she risked suggesting, in an essay of that name, that they obscured a significant meditation on the limits of free will.

Without buying into that argument, a recent re-reading of a now-obscure novel but another unfashionable French author encouraged me to enquire if we should also immolate Françoise Sagan.

Francoise Sagan in her Jaguar (coat and car)

In her day, (1935-2004), Sagan was a household names. A cartoon of the time showed a village shopkeeper giving her weekly order ; a dozen bottles of the most popular mineral water, a case of Beaujolais; a carton of the best-known soap powder; some scratch cards for betting the horses - "...and four or five Sagans."

Not since Colette had any woman so effectively turned a gaudy personal life to literary account. Apparently determined to "live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse," she wrecked cars, sniffed cocaine, gambled recklessly, slept around with both sexes, and treated the artistic establishment with contempt. They let her get away with it. "A charming little monster," chuckled Nobel Laureate François Mauriac.

Bonjour Tristesse, written when she was eighteen, created, in its heroine Cécile (no last name - so cool) an archetype that every precocious Parisienne strove to imitate. Arrogant but romantic, hard on the outside but as soft inside as a fondant chocolate, Cécile derails the sex life of her playboy father for, as she sees it, his own good, but is won over by his new lover who reaches her exacting standard.

La Chamade – it can mean a heartbeat, but also the drum roll signifying retreat - was the sixth of Sagan's twenty novels. Published in 1965, it displays all the elements that would sustain her for another three decades. Her characters, wealthy and urbane, inhabit a "dark, glowing, seductive" Paris that the city hides from most of its citizens. Journalists, publishers, men successful in some vaguely defined enterprise, or just plain rich, they meet at dinner parties or soirees, where relationships form, break up and re-form in an atmosphere as superficially polite as a minuet.

Among these people, to feel too deeply about something or someone, or to know too much about a subject - and, worse, to show it - is Just Not Done. The protagonist, Lucile (again no surname), young mistress of wealthy Charles, hears a piano concerto on her car radio but wonders "Was it by Grieg, Schumann, or Rachmaninoff? Certainly some romantic, but which one? This uncertainty annoyed her and pleased her at the same time. The only cultural icons she liked were those that she knew by heart."

There is no Eiffel Tower in their world, no Arc de Triomphe, no Center Pompidou. If they refer to such places, it is in the code of those who are branché ; plugged in; switched on. The Arc de Triomphe is l'etoile - the Star - because of the streets radiating from it, and the Pompidou Centre le Beaubourg, since it occupies a former square of that name. Sites favoured by tourists are shunned as a matter of course.

Whether one lives in the first or second arrondissement, close to the Opéra and the Louvre, the snobby sixteenth, with its vast antique-filled apartments, or best of all, in subdued and leafy Neuilly, is of crucial importance, as is a distinguished ancestry. Lucile is identified only by her Christian name, unlike Charles, who is always Charles de Blassans-Lignières, his family vastly more important than his money.

In a weak moment, Charles indulges Lucile by letting her have an affair with poor but glamorous young journalist Antoine, only to have her fall in love with him. The relationship is charted not in descriptions of their sex life, about which Sagan is reticent, but in details of the places they live and work. Describing how Lucile is forced on a wet November day to travel by public transport, Sagan evokes a bus stop on Place d'Alma as meticulously as a mansion on Ile St Louis. Ignorant of the rules for boarding the bus, she shelters in "a little booth at the bus stop ...jammed with shivering people, sullen and nearly hostile." All in all, a nightmare, the social cost far greater than the emotional pain of leaving her well-heeled protector.

At the end, she returns gratefully to Charles, the vehicle of their reconciliation his invitation to a black-tie-only concert. "They're scheduled to be playing that Mozart concerto for flute and harp that you were always so fond of," he murmurs seductively. Amidst the glitter of crystal and the elegance of St Laurent, she resumes the seat she was destined to occupy.

Sagan could have drawn Lucile as no more than a parasite. Instead she invites us to see her as a true hedonist, motivated by a need to experience pleasure and, in doing so, to share it with others. More geisha than girlfriend, she is born to be a rich man's darling. Charles, by keeping her on too short a leash, bears some of the responsibility for driving her into an affair, just as Antoine's preoccupation with his career pushes her back into the arms of Charles. Either way, she isn’t to blame. As critic Adam Gopnik observed, “The French believe that all errors are distant, someone else’s fault.”

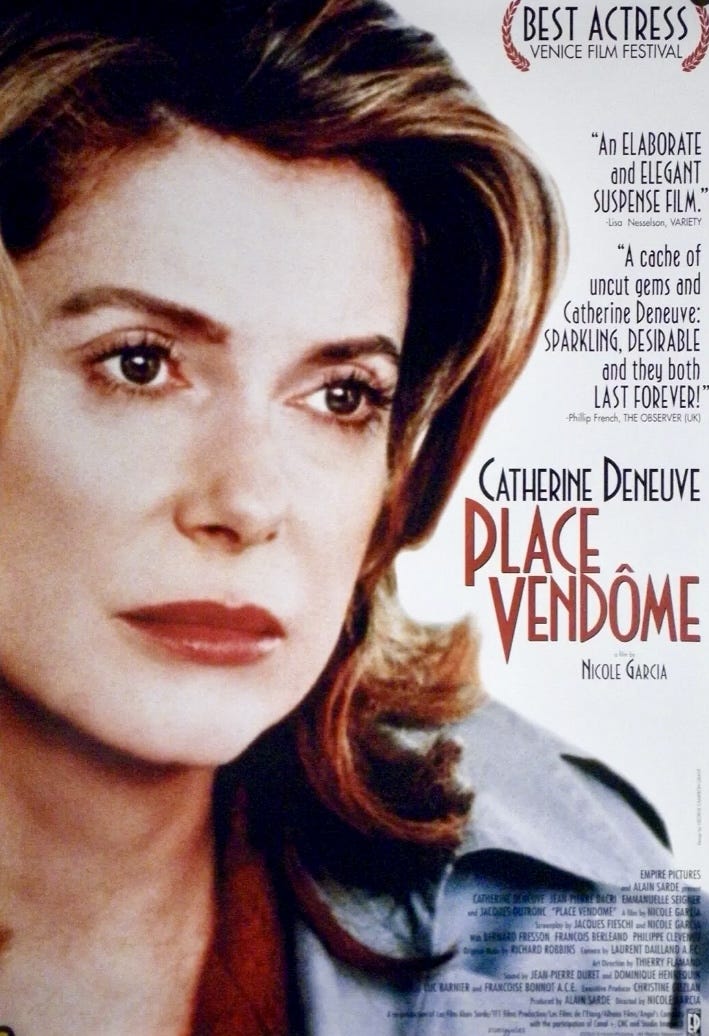

Catherine Deneuve learning how to catch a bus in the rain in LA CHAMADE.

In 1968, La Chamade was filmed, with Catherine Deneuve as Lucile and Michel Piccoli as Charles. I wrote this review for Geoff Gardner’s FilmAlert blog. What Cavalier chose to use and what to discard makes for an interesting comparison.

The key scene of Alain Cavalier’s La Chamade, retitled Heartbeat for its brief US release, comes halfway through. Catherine Deneuve, seated at the bar of a Paris café, is reading William Faulkner’s The Wild Palms. A passage so impresses her that she reads it aloud to the other customers. Whatever one does, urges Faulkner, be it to eat or drink or make love or take a dump, one should enjoy it to the limit, since you’re a long time dead. The dour office workers look up from their Croque Monsieurs and burst into spontaneous applause.

Traditionally, the nouvelle vague transformed French cinema, so by 1968 such well-made films as this, based on popular novels and featuring major stars, should have disappeared, consigned to the genre belittled by François Truffaut in his essay Une Certaine Tendance du Cinéma Français as “a cinema of...” pause to sneer “...Quality.”

In fact, they continued to flourish. Designer Jacques Dugied’s recreation of life in the satellite community of Neuilly shows not a ripple of the new wave. As for Pierre Lhomme’s lighting, one suspects he would rather eat glass than engage is anything as vulgar as a hand-held shot.

Deneuve’s Lucile has known only luxury. As the mistress of Charles (Michel Piccoli), she is the classic bird in a cage not so much gilded as solid gold. At a theatre party, however, her eyes meet those of Antoine (Roger van Hool), young lover of their friend Claire. Charles intercepts the look and decides to encourage a liaison as a kind of treat for her, like a gourmet proposing a hamburger.

Predictably, it all goes wrong. Pressured by Antoine, she abandons leisure and Neuilly for his attic apartment and a job in the basement of his newspaper. Were it not for the job, however, she would never have read The Wild Palms and experienced her moment of revelation. It remains only for Charles to dangle before her the prospect of returning to the cage. Visiting their old home, she opens a wardrobe and finds all her beautiful clothes just as she left them. The last shot is of Lucile walking down the middle of an empty street, at home once again in the world for which she was born.

Sagan gave readers a story of beautiful people facing emotional conundrums which they solve by socially acceptable mean. The most extreme crime passionel in this world is to show emotion. In a well-directed scene at a cocktail party, Charles’s friends silently assemble to show their disapproval, not of Lucile, but of Antoine for having seduced her and dumped Claire. Just not done, old boy.

Appearances and particularly clothing are at the heart of La Chamade. Lucile’s wardrobe, furnished by Yves St Laurent, is of the essence. When she returns to Neuilly to say goodbye to Charles, she’s wearing some unflattering jeans. They, more than anything else, signify that he’s lost her. Occasionally the Vogue-ishess achieves a slightly comic edge, as when, taking public transport for the first time, she tries to squeeze onto one of the old-fashioned Paris open-backed buses, her sole concession to the weather a coat probably worth as much as the bus itself.

Later, she faces a Top Person’s Crisis when, as she sells some of her jewels, a wealthy American offers to replace them if she will have lunch with him – and more? Rather than her slapping his face, they step outside and share a cigarette . She’s tempted, since, he is, after all, a gentleman - One of Us. But the column in the middle of Place Vendome reminds her that, in the first passion of their affair, Antoine took her to the top to show her that there is more to Paris than Neuilly. Though she turns him down, a life of l’amour et d’eau fraiche no longer seems quite so appealing.

At 25, Deneuve had already made Belle de Jour, Les Parapluies de Cherbourg and Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, but in none of them is she as beautiful as in La Chamade. Thirty years later, perhaps not by coincidence, she returned to Place Vendome in Nicole Garcia’s eponymous film, now the alcoholic proprietor of a failing jewelry business – and, it might be surmised, a vision of Lucile as she could become in middle age. It’s in many respects a more glamorous portrait but the flush of a drinker has replaced the innocent blushes of La Chamade and what William Blake called “the lineaments of gratified desire.” I know which I prefer.

Excellent piece. Just seeing the beautiful and elegant catherine deneuve brightened my day. Thanks as always.

Oh gawd, really wish predictive text would stop correcting me... That should, if course, be tip-off.