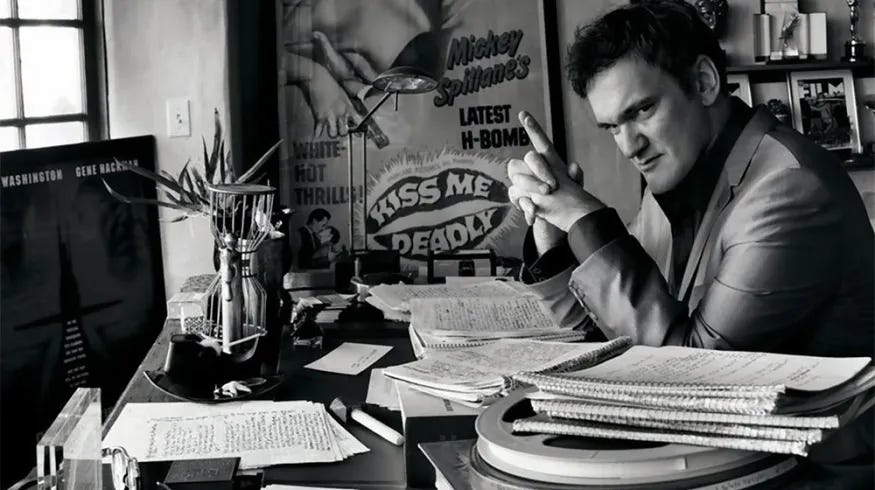

Quentin Tarantino, on of the rare writers who saw his work on screen more or less as he wrote it.

Browsing through some old files recently, I stumbled on a folder marked “Miscellaneous”. What tumbled out were articles I’d written in the days when my time was spent wandering, bewitched, in the msty groves of the movie business. Most of the pieces have dated badly, but this one, dating from around 1996 and written for the organ of the international writers’ magazine PEN, still bears a certain relevance. Some thing never change, and what William Goldman succinctly said of Hollywood at the time when he wrote Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, still applies today. “Nobody knows anything!”

ON ADAPTATION

What’s the first thing you do when you want your novel adapted into a successful film? Well, I suggest you buy a hat.

Why a hat? Let me explain.

The other day, I had cause to talk to a publicist at the PR company, PMK, who handles the actor and director Woody Allen. I asked about the demarcation in responsibility between PMK and Allen’s company, Sweetland.

‘Demarcation?’ the guy said uneasily. You could see he’d never heard the word.

No shame in that, I suppose - though it resonated ominously with a New York Times report that, in a snap test in reading and writing English sprung on a hundred graduating high school students in suburban New York the week before, 98 failed.

What’s this got to do with selling your book to the movies? Just that, if you’re dealing with the United States, you had better know that not only your audience but the professionals who hold the purse-strings may well think that the people of Britain speak French, that Austria is an island in the south seas inhabited by kangaroos, and Moby Dick is a sexually-transmitted disease.

Any book on screenwriting will explain how to structure your book as a potential screenplay. Introduce your main character and a romantic interest for him or her in the first seven screen minutes, respect the three-act format, build through a series of climaxes to a conclusion, ideally realised in terms of action, and follow with a shock ending before the clinch.

All this is simple. The hard part comes when you sell your story.

Because film people don’t read. Most studios are in the hands of people in their early thirties who’ve never seen a live play nor a film older than five years, and not cracked a book since high school. They have people for that sort of thing ; usually women called ‘D’ girls - ‘D’ for development. They boil down the book into a sentence, even a phrase. James Cameron, director of the Terminator films, famously sold his latest epic, destined to be the most expensive production in movie history, as ‘Romeo and Juliet on the Titanic.’ David Cronenberg of Crash and other grisly fantasies joked that his film Dead Ringers, in which Jeremy Irons played doctor brothers, was ‘like Rocky, but with twin gynaecologists.

Jeremy Irons and Genevieve Bujold…and, well, Jeremy Irons again in Dead Ringers (1988)

So your book will stand or fall on its concept - even its advertising slogan; maybe just its title. Some of the biggest movies in production now are based on indifferent books with titles that will lure you into the cinema on the basis of a major star and an intriguing name: Robert Redford in The Horse Whisperer; Clint Eastwood in Nights in the Garden of Good and Evil.

A former assistant to the vice-president of production at a major Hollywood studio told the New Yorker magazine last month that, in choosing a film project, executives weigh ‘in descending order of importance, whether another studio is interested in it; whether a major talent is attached to it; whether a major director is attached to it; whether a major writer has written it; whether a major production company is shopping it. Only then do they consider whether the project’s any good.’

There are exceptions, of course. This year’s major British success and Oscar winner, The English Patient, was based on an intricate, unconventional and ultimately tragic novel by Canadian Michael Ondatjee. Surely if a story this complex could become a hit movie, anything is possible. But ask its producers about how they raised the money, and brace yourself for a recital of horrors - culminating perhaps in writer/director Anthony Minghella describing how Columbia wanted to replace Juliette Binoche as his compassionate nurse with sex-pot Demi Moore - a variation, this, on a famous Hollywood story about a Disney life of Beethoven.

‘We love your script,’ said the executive. ‘But there’s just one thing. We’d rather he wasn‘t deaf.’

Maybe the new investment of lottery money in the British film industry, announced with much flourish at the Cannes film festival this year, will re-introduce intellect and literature to the film business, and restore the values of story-telling and character that produced The Third Man, The Red Shoes and Dr. Strangelove. But don’t count on it. Alan Plater, scriptwriter of The Biederbeck Tapes and other British TV successes, once recalled a production meeting interrupted by a message from the author of the book being adapted. In the most strenuous terms, he complained about the treatment of his book.

‘Are we under any contractual obligation to take note of his objections?’ the British producer asked.

‘None whatsoever.’

‘Then tell him,’ he said, turning briskly to other matters, ‘to go shit in his hat.’

Now aren’t you glad you bought that hat?