You can tell a lot about the health of the retail sector by the speed and frequency with which shops open and close on our street. In particular, I’ve watched the gradual demise of the bookshops that once lined rue de l’Odéon, (including Sylvia Beach’s original Shakespeare and Company, now a dress shop), until only four survive. Before the holidays there were five, but I noticed yesterday that the movers are in at Librairie Amélie Sourget, the elegantly empty windows of which used to grace the lower end of the street. As that area is increasingly devoted to cafes, I suppose we can expect another tourist-luring watering hole.

I wrote the following some years ago as an early exercise in private printing, and revised it during the Covid lockdown for Geoff Gardner’s estimable FilmAlert blog.

https://filmalert101.blogspot.com/

I hope he won’t mind me reproducing it once more as a lament for the accellerating decline into desuetude of a once valued intellectual resource.

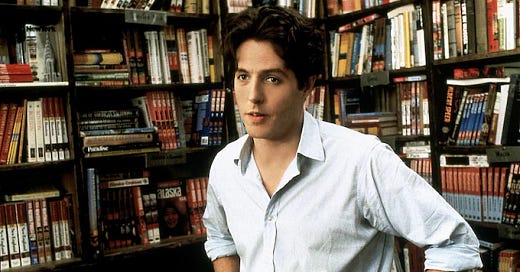

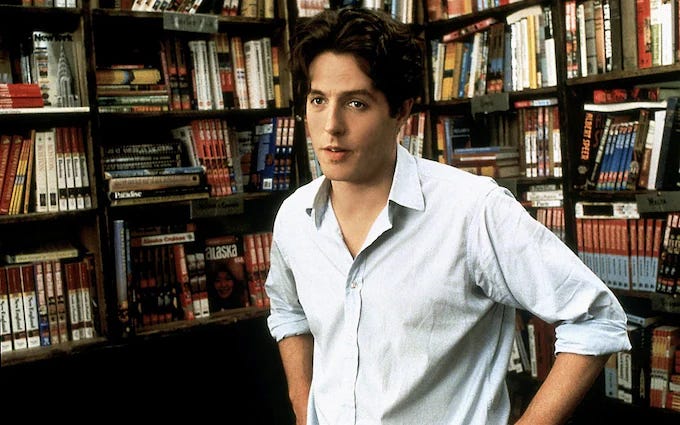

Hugh Grant as the proprietor of an unprofitable travel bookshop in Notting Hill.

With the boom in Zoom and Skype telecasts from home, instigated by Covid -19, the private library is once again in vogue as an interview background. But those shelves of well-thumbed classics in full Morocco are gone. Instead, the jumble behind most spokespersons suggests a panic visit to the nearest charity shop.

They could have learned from the cinema, where the owning, collecting and selling of books has always been fraught with hazards. Charles Boyer, a serious bibliophile (Fallada, Zweig), was amused, playing the High Lama in a remake of Lost Horizon, to find that Shangri-La’s library, supposedly the repository of all earthly wisdom, contained mostly Reader’s Digest Condensed. But classic Hollywood would have regarded even these as highbrow. Barbara Stanwyck as “Sugarpuss” O’Shea in Ball of Fire shrugs off the library of encyclopedist Gary Cooper. Hefting a tome, she says “I’ve got one like this at home – with a radio in it.”

Tucked up an alley, open at irregular hours and staffed by dodderers or curmudgeons, movie bookshops traditionally harbour crime, even treason. In The Big Sleep, Bogart played with the cliché. To sniff out a lending library of high-class porn, he adopts a camp voice, turns up the brim of his hat, looks over the top of his spectacles and enquires after editions of Ben Hur. Chandler’s original confronts him with a vendeuse with “the fine-drawn face of an intelligent Jewess,” but Howard Hawks and William Faulkner are more inventive, substituting the most ravishing bookseller imaginable, a young Dorothy Malone. Customers being scarce during an afternoon downpour, she puts up the “Closed” sign, removes her horn-rims, lets down her hair, and repairs to the back room with Marlowe and a bottle of rye. Ah, if only....

Dorothy Malone and Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep.

Movies occasionally smuggle in a real bookstore. Paris’s Shakespeare and Co. – its modern incarnation, not the original – features in Before Sunrise. Joe Danté used LA’s venerable Cherokee Bookshop for his werewolf film The Howling, and, moreover, gave a cameo to science fiction completist Forrest J. Ackerman. Alfred Hitchcock, after informing the owner of San Francisco’s Argonaut Books “This is the way a bookshop should look,” re-built it, larger and lighter, for Vertigo. Renamed the Argosy, the studio version is totally convincing, even to its front window appearing to reflect traffic on busy Powell Street.

Most designers prefer a backlot creation. For the “divinely sinister” Greenwich Village bookstore where fashion photographer Fred Astaire meets Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face, Stanley Donen fabricated Embryo Concepts, specialising in books on philosophy - surely a guarantee of speedy bankruptcy. It shares a quality common to most invented bookstores, an unrealistic amount of space. Actors never browse. They act or dance, and that takes room. Books must also be loosely shelved to allow for that chestnut of a volume removed to reveal an eavesdropper in the next aisle.

Movie book people come in all shapes and sizes, but are uniformly unsuccessful. An inept Hugh Grant is rescued by Julia Roberts from his failing travel bookshop in Notting Hill. Isabel Coixet’s The Bookshop shows privilege and prejudice forcing newbie proprietor Emily Mortimer out of an English village. Books in profusion, rather than conveying learning and intelligence, more often suggest a remoteness from reality that is sometimes sinister, and often pathetic. Angel Henry Travers reveals to James Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life that Donna Reed, having failed to marry him in his alternative existence, became an “old maid” and -the shame of it! - a librarian.

Very occasionally there’s a star. In Roman Polanski’s The Ninth Gate. Johnny Depp, in real life a collector (Beat-iana) who should have known better, plays the world’s least likely scout or “runner”. Typically, these shady individuals sport a three-day beard and soup stains down their shirt – the seedier the attire, the greater likelihood of bargains - but Depp’s Dean Corso is a fashion plate who banters with the concierges at Paris’s best hotels, and is able, with equal expertise, to nail both devil worshipper Lena Olin and a first edition Don Quixote.

In 1938, screenwriter Harry Kurnitz, as Marco Page (marque-page = French for bookmark) created husband-and-wife runner/sleuths Joel and Garda Sloane for his novel Fast Company. MGM filmed it the same year, hoping to exploit the Thin Man vogue. Fast and Loose and Fast and Furious followed, neither much good, audiences preferring the bibulous to the bibliophile. Such films generally hinge on a manuscript, usually by Shakespeare, a writer of whom some in the audience might actually have heard. It wasn’t until 2018 that movies caught up by celebrating a genuine bibliofraud in Lee Israel, faker of celebrity letters, impersonated with pungent authenticity by Melissa McCarthy in Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Finally, I confess to a soft spot for Nora Ephron’s You’ve Got Mail, if only for her chutzpah in recycling Lubitsch’s The Shop Around the Corner. A single scene justifies its overall soupiness. Tom Hanks, proprietor of the chain about to put Meg Ryan out of business, browses her rare book cabinet, and finds the price of one item startling. An assistant ennumerates the book’s collectible points, including tipped-in colour plates.

“Is that why it costs so much?” enquires Hanks.

“That’s why it’s worth so much,” the assistant corrects him. Precisely.

A footnote. The relationship between bookselling and espionage, explored by Graham Grenne in The Human Factor and Otto Preminger’s film of the book, isn’t entirely fictitious. In 1961, London booksellers Helen and Peter Kroeger were unmasked as Soviet agents Lona and Morris Cohen. After Leontine’s death in 1992, she was honored by having her likeness on a stamp – as close as any bookseller has come to immortality

.

Love this, John … not the demise of Bookshop No 5 in your lovely neighbourhood, of course. That’s a sad turn of events - though adventures in retail can run their course (JoJo and I relished our 5 years as deli owners but a sixth would have been too much). More, I love the exploration of book shops and bookish characters in fiction. I’ve written a couple of pieces that played into that space and your loving lament for the passing of the character-filled bookshop inspires me to ponder another. Happy Wednesday. Barrie