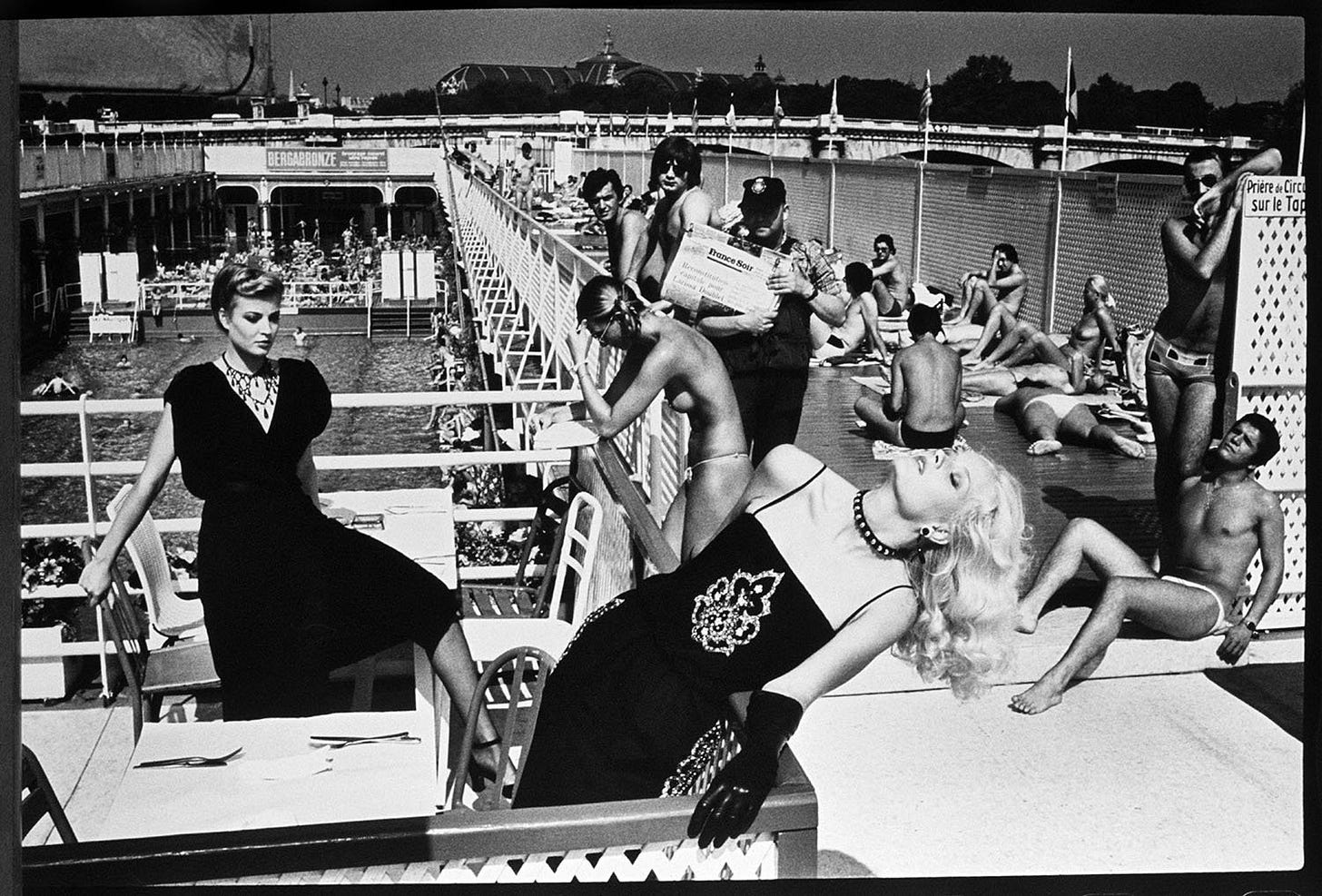

Piscine Deligny at the height of its popularity in the nineteen-fifties.

If the current Olympic Games have no other lasting result, they will at least have persuaded Paris to do something about the cleanliness of the Seine. To show that the river is no longer , as someone described it back in 1844, "sale, troublé, souvent fétide et malsaine" (dirty, turbid, often foul-smelling and unhealthy), various city officials, including mayor Annie Hidalgo, have been filmed gingerly immersing their bodies its waters – protected, naturally, by neck-to-ankle wet-suits.

In doing so, Mme. Hidalgo is just reflecting the attitudes of her constituents, since, about the value of swimming, the French are ambivalent. They admire, praise, contemplate, study, paint and photograph the waters of their rivers and beaches - but swim? Not so much. A seaside resort is known as a station balnéaire, from the Latin statio, to stare - literally "to stand upright" - and balneum: bath. According to one definition, it's “a place by the sea, or any other place with baths fitted out for the reception of vacationers.” Swimming isn’t mentioned.

Resorts faced with this prejudice against immersion resourcefully invented Thalassatherapie: health treatment using products of the sea, and named for the Greek goddess who ruled it. A typical regime begins with a battering from a stream of salt water at fire-hose force, followed by a bath in lukewarm seawater mixed with powdered seaweed and other marine organics, an experience not unlike bathing in gravy. After a shower and body massage, the client is laid out next to an Olympic-size swimming pool and invited to contemplate an ocean view while soothing music and filtered sunlight lull jangled nerves. One has absorbed as much of the ocean's bounty as if one had swum the English Channel, but never actually touched toe to wave - to the French an ideal encounter with the sea.

In the nineteen-twenties and 'thirties, when Germany could boast 1360 public pools and Britain 800, Paris had a mere fifteen, and the entire country not many more. Until the nineteen-sixties, Parisian swimmers had to be content with the few public pools or piscines scattered along the river. Often little more than half-sunken barges, they offered river water from which the larger pieces of debris and most dead animals had been removed.

At one time, the Seine supported twenty such pools, of which Piscine Deligny, next to the Place de la Concorde, was the most fashionable. Essentially a barge filled with water, it became so popular that the owners added oriental-style terraces and cafés. Timber came from the Dorade, the steam-boat which, when Napoléon's body was returned from Saint Helena to Paris in 1840, carried it up the Seine for re-burial.

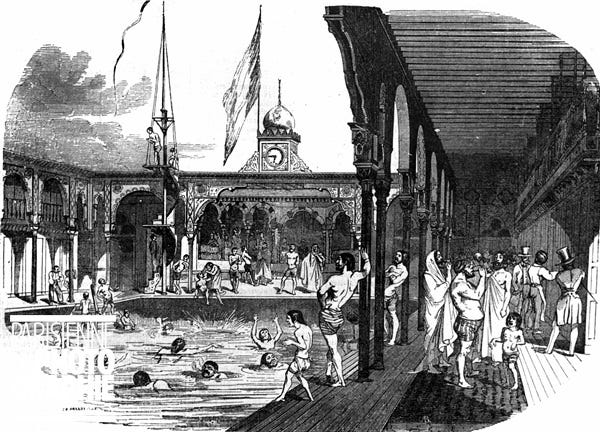

The Deligny in 1845.

During the belle epoque, men-about-town strolled there in the afternoon to smoke cigars and take coffee, but mostly to admire the women in their clinging wool maillots de bain. Marcel Proust's mother was among them. He remembered her "splashing and laughing there, blowing him kisses and climbing again ashore, looking so lovely in her dripping rubber helmet, he would not have felt surprised had he been told that he was the son of a goddess."

The Deligny provided private cabins, technically for changing clothes but often misused. One habitué reminisced, "American girls learning French at the Alliance Française, just three Metro stops away, would come down to the pool. They seemed to enjoy perfecting their French with me. Sometimes I would take the girls into my cabin to continue their French lessons. It was charming, if not altogether comfortable."

The 1900 Olympic Games used the Deligny for its swimming and diving events, and better filtering was installed in 1919, but it took the German Occupation to achieve a real upgrade. The Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe officers who had exclusive use of the facility demanded it.

The Deligny in the decadent ‘eighties.

Post-war, the Deligny became a popular gay hangout. A member of the National Assembly complained that, crossing the bridge on his way to a sitting, he was distracted by the sight of near-nude toy boys sunbathing below. Rather than suggesting he avert his eyes, the owners screened off the terrace, but these indignities were too much for the timbers that had borne the bones of Napoléon, and, in the early hours of July 8, 1993, it ignominiously and mysteriously broke up, its rotted timbers settling to the mud.