Well, it had to happen. Make-over fever has infected one of the last of the seedy left bank hotels, La Louisiane.

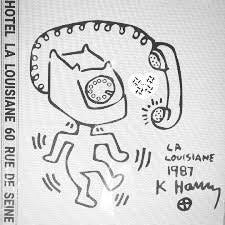

Almost, it seems, overnight, the drab brown façade below the art deco lettering of the name blossomed with glossy new trim in red-brown cinnabar. And though it never hitherto trumpeted its cultural credentials, the window looking into the lounge now reproduces an endorsement from artist Keith Haring.

One by one, the city’s traditional boho boltholes have succumbed. The formerly nameless “Beat Hotel” on rue Git-le-Coeur, hang-out of Corso and Ginsberg, where William Burroughs invented the “cut-up” method to create Naked Lunch, is now the four-star Relais Hotel Vieux Paris. They change the sheets daily rather than, as formerly, once a month, and there are baths en suite for each room where one alone was once considered sufficient for the entire hotel, and had to be booked a week in advance.

One of the longest hold-outs, the legendarily cheap Hotel Henri IV on Place Dauphine, has just emerged from a lavish make-over into luxury apartments. It remains to be seen if the Louisiane will follow suit. Paris’s nearest rival to New York’s Chelsea, it’s as much cultural centre as hotel. The list of artists who lived there begins with British writer and editor Cyril Connolly in the nineteen-thirties. He and his mistress occupied one of its three famous round rooms, where they kept pet ferrets, feeding them raw horse’s liver and tracking them from bells attached to miniature harnesses.

Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir lived there during and after World War II. They also found a room for a waif named Juliette Gréco. Going barefoot, leaving her hair long rather than paying a coiffeur, wearing mens’ clothes because they cost less than dresses in second-hand stores, she created, through chance and poverty, the style that epitomised post-war St-Germain-des-Prés, Greenwich Village and London’s Soho.

Gréco shared her room with an equally lost and beautiful Anne-Marie Cazalis, with whom she was controversially photographed in bed. “Yes, I have loved women – physically,” she admitted at a time when such revelations were still scandalous. “You can love a woman as easily as a man.”

The man who would become the love of her life arrived in May 1949 for the International Jazz Festival that revived Paris’s moribund modern jazz scene. Gréco couldn’t afford a ticket so Michelle, wife of Boris Vian, took her backstage, where she first set eyes on Miles Davis. “I saw him in profile. An Egyptian god. I had never seen such a handsome man. Like a Giacometti.” He moved in with her, ensuring that the Louisiane would become a home-from-home for generations of jazz musicians. Gréco’s room had one of the hotel’s rare baths, and she remembered Davis sitting in it, playing music by the composer he called his “darling” – Johann Sebastian Bach.

In his film Round Midnight, Bertrand Tavernier immortalised those years, when American jazzmen played nightly in basement boites de nuit and returned to the Louisiane to cook red beans and rice on a hotplate. Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Lester Young, Charlie Parker and John Coltrane are all said to have stayed there, though evidence is often sketchy. The supposed occupancy of Ernest Hemingway and Salvador Dalì is particulary suspect, since both were known to prefer the more cushy Meurice or Ritz.

Nobody who experienced them is really nostalgic for the days of the cheap hotel. But for those of us who first explored Paris on a shoestring, those threadbare sheets smelling of bleach, the flimsy cotton blankets, dubious bedspreads and loathsome carpets, the furtive scuttle of cockroaches as you turned on the light, and the unerotic bump bump bump on the wall from the couple hard at it in the next room, are inseparable from the thrill of sipping that first express or biting into a baguette.

And when truth and legend conflict…? You’re kidding! Jim Morrison? In this actual room?

You are a mine of information John. So interesting.

“Hier encore j’avais vingt ans ... “