Juliette Greco, in costume, with the church of St Germain des Pres in the background.

The most popular theme for a walk around Paris is no longer the Lost Generation or even the Montmartre of Picasso; instead, what tourists want to know more about is the Nazi occupation of France from 1940 to 1944.

Far more interesting is the period immediately following; the years between 1944 and 1950, when Paris raced to absorb the accumulated films, books and music which the Nazis had banned.

Joseph Wechsberg, a musician in Paris before the war returning in 1945 as a GI, found Montmartre much as he left it. “The women accordionists in the cafés were still playing their old songs and javas, the tired sidewalk painters had their watercolours propped up against the trees of the Boulevard de Clichy, and the busy, smiling little ladies [i.e., prostitutes] were patrolling up and down as of old, almost as chic as ever despite three-year-old dresses and wooden shoes.” (With leather unobtainable, shoemakers adapted the traditional peasant footwear, clogs.)

Young Parisians, however, were depressed by the squalor of the neglected city. They embraced the United States and everything it stood for. Under the occupation, a group called les Zazous had tried to imitate the style of Harlem’s pimps and hipsters. Unable to replicate the baggy tapered trousers and long draped coats of the “zoot suit,” they compromised on drooping jackets in plaids and checks, set off with a single incongruous accessory: a furled umbrella. The same style was adopted by the Mods of Britain in the ’sixties, and the bodgies and widgies of New Zealand and Australia, though neither embraced another favourite Zazou accessory, a poodle, meant as a homage to Juliette Greco’s dachshund.

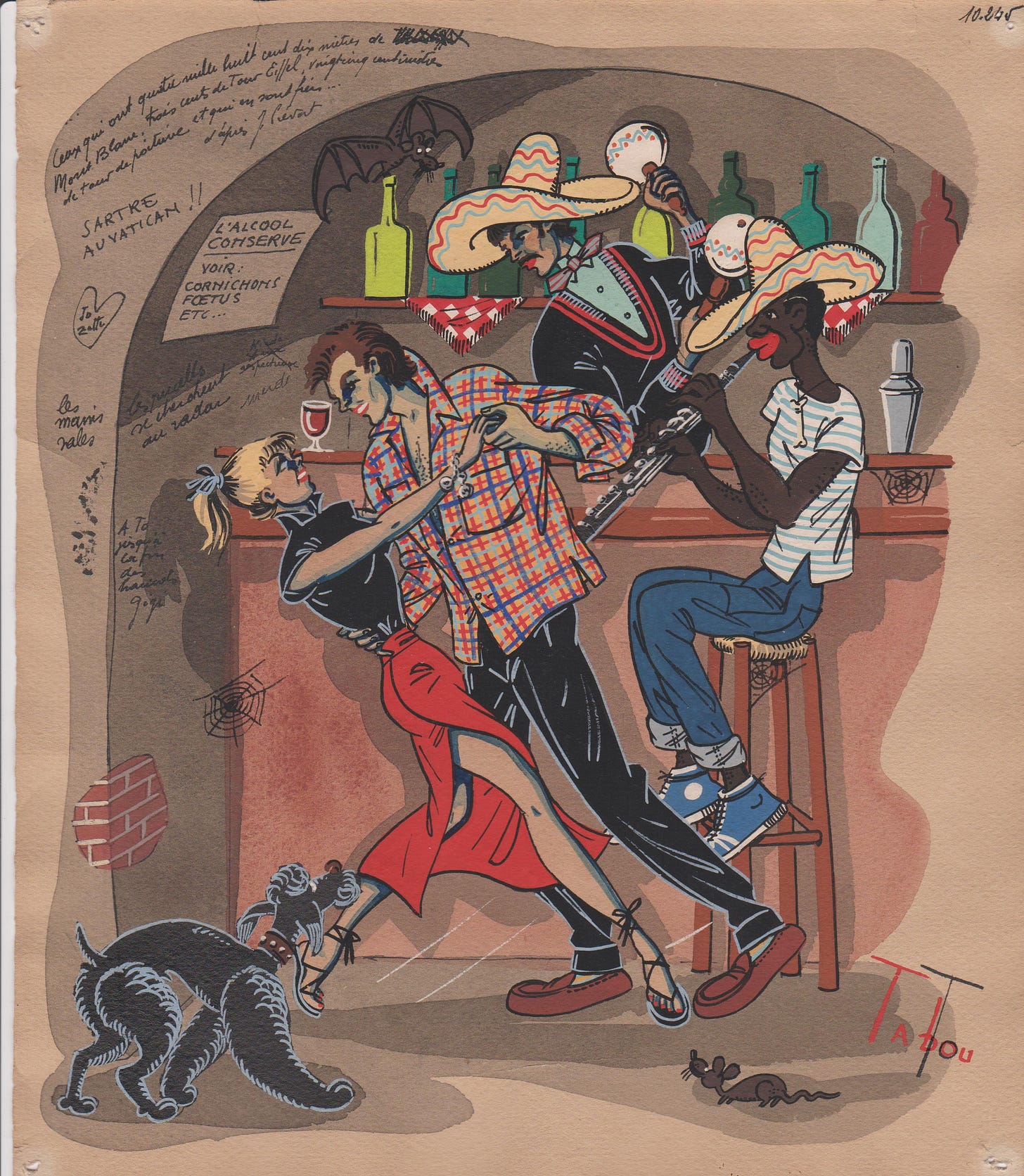

Retro-Zazou, complete with umbrella and poodle.

Lacking the leather jackets, jeans and t-shirts seen in magazines and films, they imrovised a uniform from anything that looked vaguely American: in their case lumberjack shirts, black cotton trousers, and tennis shoes, topped in winter with a loose sweater or duffel coat. The Zazous had danced to smuggled 78 rpm records or big-band swing broadcast by Armed Forces Radio. The new hipsters, jiving in the cellar clubs of Saint-Germain and Pigalle, preferred New Orleans jazz of the kind popular before the war. They called their dancing “bebop,” although it would be years before true bop, pioneered by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, arrived in Europe.

With her long black hair, high cheekbones and large mournful eyes, Juliette Greco became the poster girl for post-war ennui. In 1947, with Boris Vian, she started her own jazz club, the Tabou. It occupied a cellar on narrow rue Dauphine, in the heart of the left bank, in the basement of a café which, because one establishment in each district was designated to serve delivery men and others who worked unsocial hours, stayed open around the clock. The unventilated crypt resembled a railway tunnel, while the sweat and cigarette smoke that gathered there during a night of hectic jive made it look as if a steam locomotive had just passed through. A loaf of bread left on a table deliquesced into something resembling porridge. Locals, furious at the noise of people partying at all hours, often emptied chamber pots onto their heads.

Check-shirted pseudo-existentialists be-bopping at the Tabou in 1947.

If these people had a philosophy beyond that of having a good time, it was the ascetic process developed by Jean-Paul Sartre which he called existentialism. Few, if any, of his professed admirers had read Sartre’s writings, or, if they did, understood them. For his part, Sartre disowned his groupies. After Gréco described herself and her followers as existentialists, Sartre posted a notice at La Hune, Saint-Germain’s most fashionable bookshop, declaring “that band of check-shirted youngsters who haunt St. Germain-des-Prés [and who] came to be known as Existentialists bear no relation to me, nor do I to them.”

The bon vieux temps didn’t rouler for long. Real be-bop arrived with Miles Davis in 1949 and proved not to be to French taste. They preferred the manouche gypsy music of Django Reinhardt and the discreet improvisations of John Lewis’s Modern Jazz Quartet.

The Modern Jazz Quartet. Discreet.

After Davis and Gréco became lovers, Hollywood in the person of 20th Century-Fox mogul Darryl Zanuck snapped her up as star and bed-mate. With sex comedies and historical/literary adaptations, French cinema wandered into the doldrums from which it would be rescued by the nouvelle vague.

Against all odds, however, existentialism survived. Paris became the world capital of ideas. Simone de Beauvoir adapted it to feminism in The Second Sex; Lacan, Barthes and Debord enlarged our understanding of language and society. Will visitors, sometime in the far future, become nostalgic for those days too, and demand guided visits to significant sites? That might have given even the humourless J.P.S a laugh.

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Bauvoir. No laughing matter.